Three Years of SFDR: A Deep Dive into Article 9 with Three of Europe’s Leading Impact Investors

Since its introduction in March 2021, the Sustainable Finance Disclosure Regulation (SFDR) has reshaped the European investment landscape. Designed to enhance transparency, SFDR is part of a broader sustainable finance strategy under the EU Green Deal, aimed at achieving carbon neutrality by 2050. The regulation requires financial market participants to disclose sustainability risks and back up sustainable investment claims with the intention of strengthening investor awareness, preventing greenwashing, and accelerating financial flows into sustainable investments.1

Overall, SFDR has been met with widespread support, particularly for its transparency objectives. In fact, the EU’s consultation on SFDR found that 89% of respondents believe these transparency goals are relevant. However, 77% of respondents also highlighted key limitations such as legal ambiguities, the complexity of disclosure requirements, and challenges with data availability.2 As a result, the effectiveness of the SFDR framework has been limited, leaving the industry divided on its overall impact.

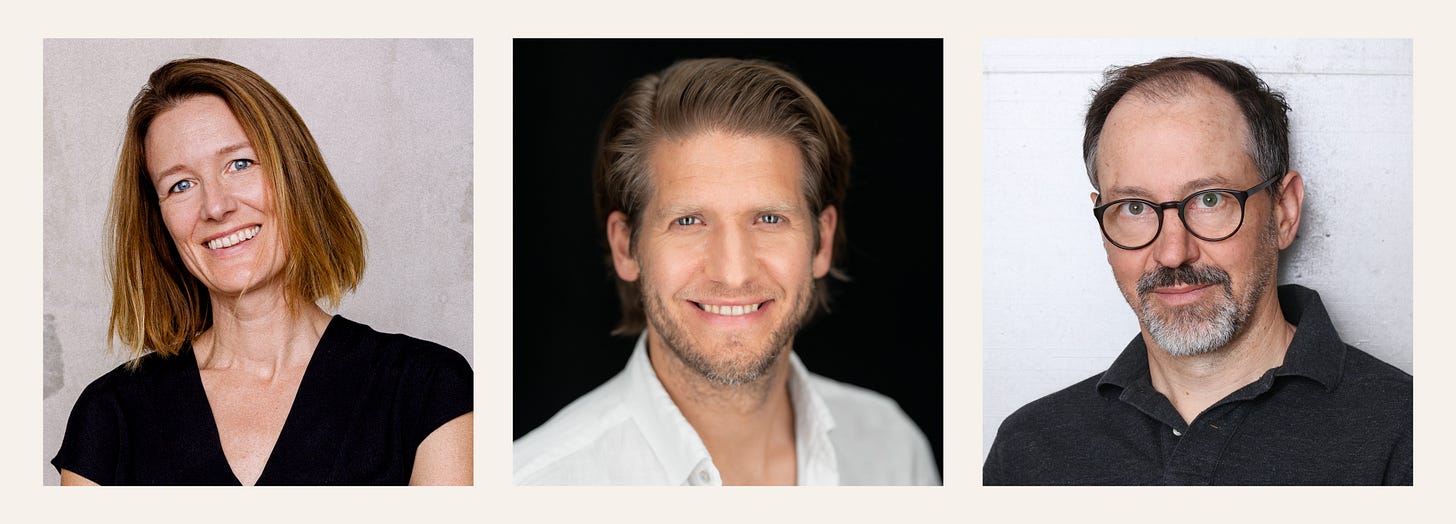

But how has SFDR played out for impact investors specifically? For funds that have sustainability at their core, particularly those classified as Article 9 under SFDR*, compliance with SFDR has required more than just meeting transparency goals—it's about balancing regulatory requirements with the authentic impact missions they pursue. To unpack this further, we spoke with three leading investors from European impact funds—Lena Thiede (Planet A Ventures), Fabian Heilemann (AENU), and Florian Erber (Ananda Impact Ventures). They offered insights into their motivations for aligning with Article 9, the benefits it brings, and the challenges they’ve faced in adapting to the regulation.

*SFDR categorizes funds into three types based on their approach to sustainability:

Article 6 funds do not have a sustainability focus, though they must disclose how they consider sustainability risks.

Article 8, or “light green” funds, promote environmental and/or social characteristics.

Article 9, or “dark green” funds, have sustainable investment as their objective.3

The Case for Article 9: Impact at the Core

For all three funds, the decision to classify as an Article 9 fund was not just regulatory but reflective of core values. Lena Thiede from Planet A noted, “We were big supporters of SFDR from the start. Its goal is to foster transparency, prevent greenwashing, and direct capital toward sustainability. Since our fund is 100% dedicated to sustainability, it was clear from the beginning that we would classify as an Article 9 fund. Who, if not us?”

Fabian Heilemann from AENU echoed this sentiment, explaining, “We aim to bring impact tech investing into the mainstream VC ecosystem. Our rigorous impact methodology goes beyond Article 9 requirements, so it was a natural choice for us. Now we need to prove that Article 9 strategies can deliver financial returns similar to Article 6 or 8 funds while offering additional impact returns.”

Florian Erber from Ananda added further nuance on his understanding of Article 9, pointing out, “The market often treats Article 9 as a label to choose, but it’s actually a regulatory requirement. For any fund positioning itself as sustainable, compliance with these disclosure standards is non-negotiable. From my view, every impact fund falls under this category.”

Yet, while every impact fund may fall under Article 9, not every fund classified as Article 9 is necessarily an impact fund. In that vein, Florian added, “As impact investors, we’ve long advocated for more capital to flow toward sustainable and social topics, and now SFDR provides a framework to differentiate between sustainable and non-sustainable investments. It’s a positive and necessary step, though not yet sufficient for impact funds.”

Benefits of Article 9: Institutional Investors Take Notice

When asked about the advantages of being Article 9 funds, all three GPs mentioned growing demand from institutional investors. Florian of Ananda pointed out, “One of our institutional LPs would have had issues investing in us if we weren’t classified as Article 9 fund. But most of our investors care more about our impact strategy as a whole than just Article 9 alone.”

Lena from Planet A highlighted that, while SFDR was meant to foster transparency, in practice, “the categories of Articles 6, 8, and 9 have been used as labels to quickly communicate a fund’s green ambitions. Some institutional investors set targets to avoid investing below Article 8 or 9. For a fund like ours, Article 9 is expected as the gold standard.”

While institutional interest in Article 9 funds is growing, Fabian from AENU pointed out that being an Article 9 fund does not necessarily make fundraising easier, especially for newer players. “There are institutional and private investors who allocate specifically to Article 9 funds, but this doesn’t necessarily make fundraising easier for emerging managers. Meeting the requirements for track record and team capabilities remains crucial.”

Challenges of Article 9: Reporting Overhead and Regulatory Uncertainty

Despite the clear benefits, there are challenges associated with Article 9 compliance. One of the most commonly cited difficulties is the increased reporting burden, particularly for early-stage companies. As Florian from Ananda pointed out, “If you have a sound impact methodology, reporting on sustainable investment objectives shouldn’t be an issue. For portfolio companies, there are approximately 20 PAI (principal adverse impact) indicators to report on, some of which can be challenging for early-stage startups, particularly Scope 1-3 emissions.”

Lena from Planet A described the first three years under SFDR as a “rollercoaster,” noting several critical issues: (1) National regulatory bodies have interpreted SFDR differently, creating an uneven playing field; (2) many cleantech innovations fall outside the EU Taxonomy; and (3) SFDR was designed with larger, listed companies in mind, making it ill-suited for smaller, impact startups. “We’re talking about teams of 5-10 people who have just tested their first product. The cost and benefit of SFDR reporting simply don’t add up, and don’t align with their reality,” Lena emphasized. Instead of overemphasizing PAI indicators, she advocates for collecting forward-looking indicators that highlight an innovation’s impact potential.

Fabian of AENU added another layer, pointing out that Article 9 requires a strong commitment to impact. “Impact-driven entrepreneurs typically thrive when working with Article 9 funds, as they often have impact measurement and reporting processes in place already. It’s more challenging for entrepreneurs who are primarily commercially driven and want to add an impact angle to attract funding from Article 9 funds. But we don’t target these founders. For us, impact intentionality is a key selection criterion.”

Advice for Impact and Climate-Tech Funds: Article 8 or 9?

When asked what advice they would give to other funds considering Article 8 or 9, the GPs offered different perspectives. Florian from Ananda advised, “If you’re serious about impact, go for Article 9. But consider the potential EU Taxonomy overhead, especially if you’re a climate fund.” Fabian of AENU echoed this, stating, “If you’re truly committed to impact, then Article 9 is the right move. It sends a strong signal to both founders and investors. But be ready to handle the additional reporting requirements.”

Lena from Planet A was more cautious, pointing out that the distinction between Article 8 and 9 may soon evolve. “The European Commission has initiated a reform process. There are various models on the table, including a four-category with a clearly differentiated impact category. If possible, I’d recommend waiting until next year for more clarity on the future of SFDR.”

The Way Forward: What’s Next for SFDR and Impact Investing?

While SFDR has been a game-changer in promoting sustainable finance, the road ahead is still filled with challenges. As the regulation continues to evolve, it will be critical for funds, investors, and regulators to find a balance between transparency, practicality, and impact. For now, Article 9 remains the standard for those serious about impact investing. However, there is significant room for improvement.

To address remaining gaps and unlock further potential in impact investing, the #UnitedforImpact initiative—comprising 55 impact investors from 16 EU countries—has proposed regulatory adjustments at the EU level. Their position paper calls for a clearer definition of impact investing to prevent impact washing and proposes a new fund category within SFDR that directly targets measurable solutions to environmental and social challenges. Additionally, they advocate for harmonizing disclosure obligations for smaller enterprises and enhancing EU funding mechanisms like the European Investment Fund (EIF) to mobilize more private capital.4

These recommendations, along with the push for a social taxonomy and the creation of a mission-driven company status at the EU level, reflect a growing consensus in the impact investing space: achieving tailored reforms and regulatory clarity is crucial for scaling investments that can effectively address today’s most pressing challenges for people and planet.

We’d love to hear from others in the impact investing community. Whether you're navigating SFDR or exploring impact investing more broadly, feel free to reach out at kelley.luyken@aurum-impact.de or comment below to share your thoughts, experiences, and questions.

Aurum Impact is an impact investing firm backed by the Goldbeck Family Office. We empower systemic change by investing in founders and funds with a clear commitment to solving today’s most pressing social and environmental challenges. Our portfolio includes impact companies such as Cyclize, Paebbl, and Voltfang as well as impact funds including Planet A Ventures, Revent, Counteract, and more.